C6.5 Essays and Reports

How to Write Essays and Reports for UK Universities?

One crucial skill taught in class for academic writing is paraphrasing:[Angry Red Bird] 1) Replace words with synonyms[Angry Red Bird] 2) Switch from active to passive voice[Angry Red Bird] 3) Restructure the sentence[Angry Red Bird] 4) Change word form (nominalisation: verb to noun)[Angry Red Bird] 5) Adjust the tense

UK universities—whether for language courses, foundation programmes, undergraduate or postgraduate studies—typically assign two types of assignments: Essays and Reports. These two have minor differences and similar formats. Universities usually specify whether to write an Essay or a Report, so read the requirements carefully. If not specified, the default is an Essay.

Title PageInclude: full university name, full programme name, student’s name, student ID, lecturer’s name, submission date, essay title. Some universities require the word count. For certain programmes, the lecturer may provide a specific title page format.

Table of ContentsGenerate automatically using Word. Lecturers can use it to focus on specific sections.

IntroductionIntroduce the background and purpose of your topic, then outline the essay’s structure (how you will approach the content). It should account for approximately 10% of the total word count. Ensure you clearly state the Aim, Objective, Purpose, or Goal—this is essential. Without a clear purpose at the start, lecturers will not understand the focus of your essay. They will usually read your work with this purpose in mind.

Main BodyThe core content has two formats:

A standalone Literature Review carries significant weight, accounting for 30% of the total marks and a corresponding proportion of the word count. UK lecturers place great emphasis on the Literature Review and References.

Essays with a shorter word count typically use the embedded approach. However, 15,000-word dissertations require a separate Literature Review, which must be referenced in the analysis section—otherwise, your data and analysis will lack evidence.

Key requirement: Maintain criticality. Adopt a balanced, dialectical approach—do not focus solely on strengths or weaknesses. When highlighting strengths, cite scholars who support this view; similarly, cite sources for weaknesses. Provide comprehensive arguments, back up each point with relevant examples, and ensure all examples are referenced.

UK lecturers prefer logical, focused essays that stay on topic. You can follow the lecturer’s guidance, so do not hesitate to ask questions. As Confucius said: "He who is not ashamed to ask is wiser than he who thinks he knows everything."

Conclusion and RecommendationSummarise the key points, echo the introduction, and reinforce the thesis. It should make up around 15% of the total word count. Recommendations must be based on content discussed in the essay—avoid irrelevant suggestions that have no connection to the main body.

ReferencesArrange references alphabetically by the author’s surname. Italicise book titles and leave a blank line between each reference. For online sources, include the URL and the access date (month and year). Note that reference formats may vary by university, but most UK institutions use the Harvard Reference Style. Detailed guidelines for reference formats and automatic reference generation tools are provided earlier.

The format is similar to an Essay, but Reports focus more on practical application—they must be linked to a specific case. Use data and charts to present case analysis clearly and persuasively. Reports require a title, conclusion, and recommendations (relevant to the content), plus an Executive Summary at the beginning.

Title PageInclude: full university name, full programme name, student’s name, student ID, lecturer’s name, submission date, report title. Some universities require the word count. For certain programmes, the lecturer may provide a specific title page format.

ContentsGenerate automatically using Word.

Executive SummaryFirst, state the report’s purpose: "The main objective of this report is to XXXXXX." Summarise the key content, research object, purpose, and significance in 2-3 short paragraphs.

IntroductionFocus on the background and purpose of the report.

Main BodyUse subheadings to organise content. If there are multiple objectives, use each as a separate subheading (e.g., 3.1, 3.2, 3.3).

Conclusion and RecommendationSummarise the key points, echo the introduction, and reinforce the core message. It should account for approximately 15% of the total word count. Recommendations must be based on content discussed in the report—avoid irrelevant suggestions that have no connection to the main body.

ReferencesArrange references alphabetically by the author’s surname. Italicise book titles and leave a blank line between each reference. For online sources, include the URL and the access date (month and year). Note that reference formats may vary by university, but most UK institutions use the Harvard Reference Style. Detailed guidelines for reference formats and automatic reference generation tools are provided earlier.

Most UK universities require one of the following fonts for Essays and Reports:

Arial

Times New Roman

Use only one font throughout. Times New Roman is recommended.

Body text: usually 12-point. Headings and subheadings can use a different size.

Generate automatically by formatting headings in Word—this is convenient and efficient.

Stick to either British English or American English—do not mix the two.

Avoid subjective pronouns (I, You, We) and contractions (can’t, don’t). Do not use question marks or exclamation marks. For example: "You don’t like your father’s pen?" is incorrect. Instead, write: "Tom does not like the pen from his father."

Note UK punctuation rules:

Replace Chinese commas (、) with English commas (,); use semicolons (;) for longer pauses.

Replace Chinese book titles (《》) with italics.

Use appropriate, academic vocabulary—avoid overly simple words (e.g., replace "like" with "enjoy/favour", "make" with "enable/create", "good" with "great/perfect") but do not use overly complex words incorrectly. Vary your vocabulary by using synonyms to avoid repetition.

Capitalise the first letter of the first word in each paragraph and the first word after a full stop.

Use 1.5-line spacing for most essays. Double spacing may be required for dissertations (e.g., at Coventry University).

Ensure consistent paragraph formatting: either add a blank line between paragraphs or indent the first line. Keep paragraphs concise—avoid excessively long blocks of text.

As this guide emphasizes: when others say "You can’t do it, it’s impossible," remember to persist in pursuing your dreams. Overcome hardships and never give up until you see the light. Those who sincerely desire and persist in their dreams will eventually achieve them. Whether learning English, writing essays, or taking exams, progress is possible with perseverance, no matter how difficult the path.

Follow your university’s or lecturer’s reference guidelines. For example, Coventry University uses CU Harvard Reference, but some programmes (e.g., accounting) may have specific requirements. Always adhere to your lecturer’s instructions, as they will assess your work.

For efficient reference management, use

refworks.com. It allows you to collect and organize references easily, especially for large numbers of sources. Access is free via your university’s institutional account. Google also offers reference tools. Detailed guidelines for reference formats and automatic generation tools are provided earlier.

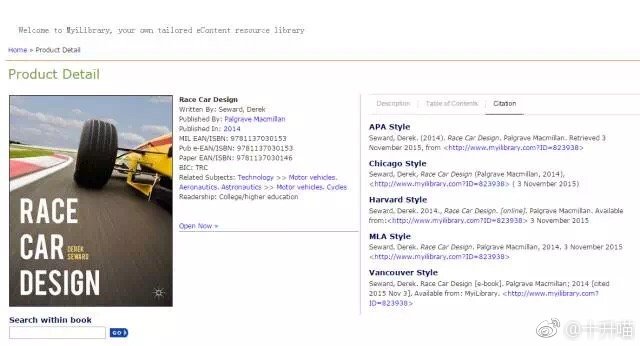

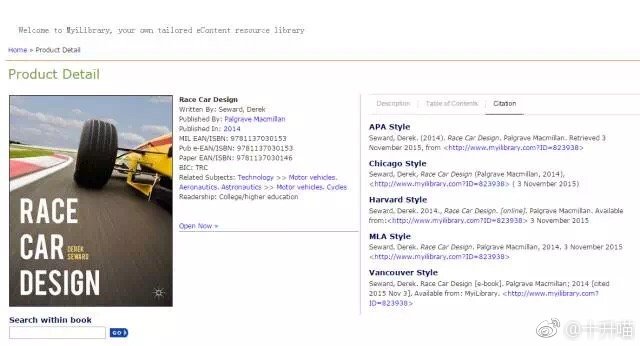

For example, Coventry University students can generate references automatically through the online library, as shown in the image below:

Harvard Reference Style:

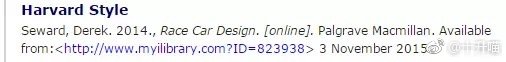

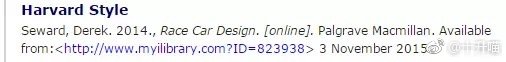

However, you will find that there are slight differences from Coventry University's own Harvard style. Coventry's format should be as follows:

Notice the differences? Apart from the brackets, the author's surname should be written in full and placed first, followed by the first name. Regardless of the first name, only the first letter (capitalized) is used, followed by a full stop. For example, what would originally be Seward, Derek (2014) becomes Seward, D. (2014) in Coventry University's format.

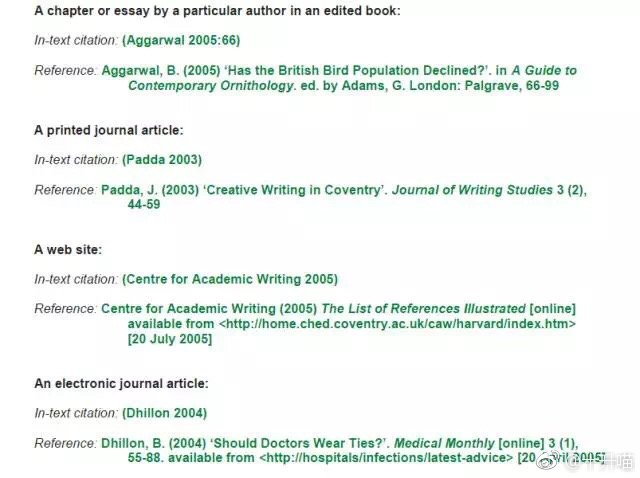

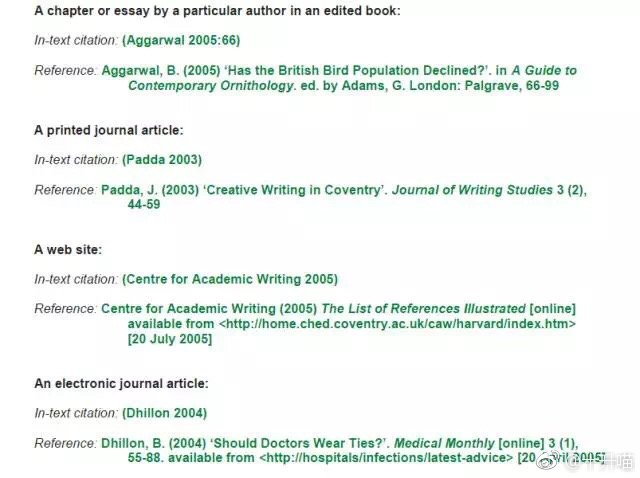

The screenshot below shows the table for Coventry University's reference section. Coventry University has its own specific reference guidelines. Another difference is in the in-text citation: the standard Harvard style is (Seward, 2014, p.30), while Coventry University's format is (Seward 2014:30).

The screenshot of Coventry University's official reference format is as follows:

Plagiarism Check

Plagiarism check refers to detecting whether a dissertation contains plagiarised content. Before submitting your dissertation, you must conduct a self-plagiarism check. Specific guidelines for recommended plagiarism check software are provided earlier. Most UK universities use Turnitin for plagiarism checks, so how can you avoid being flagged for plagiarism by the Turnitin system?

First, never copy and paste original content from online sources or books, nor just rewrite a few words. For detailed guidelines, refer to the earlier article specifically about reference formatting. A common issue: even content you have worked hard to write may be flagged as duplicate with that from another university. This is normal because everyone is writing on the same topic, and certain phrases or ideas are likely to be used by others first. How to resolve this? Rewrite. Even your own ideas need to be rewritten if they appear as duplicates. Never quote others' exact words directly—for a 3,000-word essay, you can use at most one direct quote, and it must be used appropriately. This requires strong writing skills, grammar, and logical coherence.

Supporting Images/Charts

If your essay requires supporting images or charts, each must have a title and an explanation. For example: Table 1: XXXXXXX, Figure 1: XXXXXXX. The explanation should align with the purpose of your essay, as the image/chart is intended to enhance the visibility and clarity of your arguments.

Word Count

Regarding word count: never exceed or fall below the required number. Usually, a 10% margin above or below is allowed, but some essays specify a strict word limit.

Thinking Approach

The content should not be overly subjective; it must be comprehensive and critical. Include both positive and negative viewpoints, supporting evidence, and examples. In fact, lecturers will overlook minor grammatical or spelling errors if the content is strong—so the quality of the content is the key.

Page Numbers

Always insert page numbers in your essay, typically at the bottom. I remember a classmate who submitted a several-thousand-word essay without any page numbers. Coupled with excessively long paragraphs, numerous grammatical and spelling errors, and disorganised references, the lecturer directly gave him a Fail.

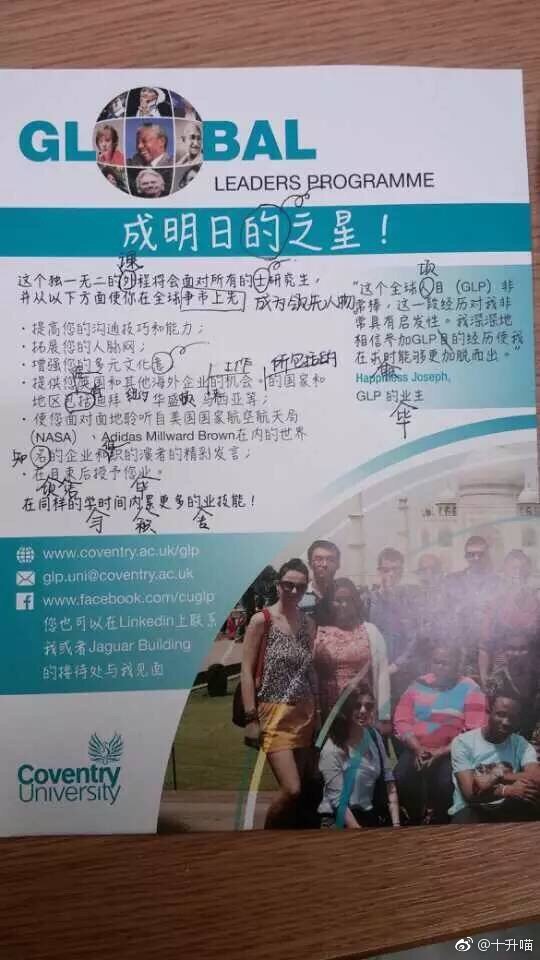

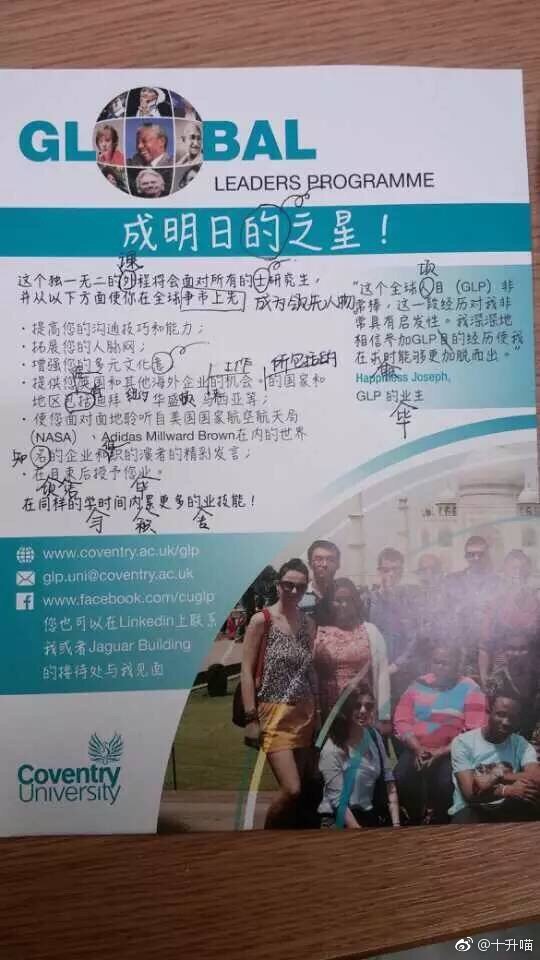

For example, the Global Leaders Program at our university, Coventry University, has a promotional leaflet with a Chinese introduction. This introduction was directly copied and pasted from an online translation tool without any modifications, as shown in the image below:

It’s obvious that the Chinese on the leaflet contains numerous grammatical errors. When it comes to grammar, what sticks most vividly in my mind is this Chinese promotional leaflet for the Global Leaders Program (GLP)—its Chinese is so poorly written that it’s laugh-out-loud funny, a complete mess. My classmates and I then got creative and enthusiastically set about correcting its Chinese grammar with wild ideas.

While roaring with laughter, we should actually think deeply: such a large university, now ranked 15th in the UK’s Guardian University Guide, really can’t handle Chinese grammar? With so many Chinese teachers, none could fix it? No—this was intentional by GLP. While entertaining students, it subtly delivers a reality check: this is exactly how native English speakers feel when reading our English essays—they find them equally absurd and amusing.

The university’s GLP was genuinely anxious for those students who came to the UK but still spoke fluent Chinese. So GLP waved its arms vigorously, calling out: “Come on, kids! We can help you improve,” and then your money would happily flow into their pockets. GLP definitely won with this clever idea—it successfully attracted many of us to join.

This reminds me of another example. During a group discussion in my class, our group was all Chinese, and everyone spoke in Chinese. Why? Because whenever someone suggested discussing in English, a few members would say: “We’re all Chinese—why speak English?” Let’s be honest, take a look at your classmates and friends around you—there must be people like this too. It reminds me of a cold joke I saw on Lengtu (a popular Chinese meme platform): “A guy who studied abroad for several years came back. His English wasn’t great, but he spoke Northeast dialect, Cantonese, and other local dialects extremely fluently.”